Siena & Florence 14th Century

Florence and Siena best represent the rise of what we now consider a city. Both of these towns were republics, governed by members of the guilds rather than by the nobility. These cities were communes, a collective of people gathered together for the common good. They were fierce rivals and challenged each other to advance in building civic halls like the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence (Fig. 15.2) and the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena (fig. 15.3). both city halls feature crenellations on rectangular forms; and they both face campos, large squares.

They also supported the emerging monastic orders and built churches expressly for them such as Santa Croce for the Franciscans (Fig. 15.7) and Santa Maria Novella for the Dominicans in Florence (Fig. 15.8); Siena also built separate churches for these two orders. Similarly, the cities each built cathedrals (Fig. 15.5) claiming to be more beautiful than the other. Siena's Cathedral was of French Gothic design: Florence's Santa Maria Novella was more austere, with plain façade and simple interior. Siena and Florence were both thought to be watched over by the Virgin Mary, as evidenced by the frescos of the period.

They also supported the emerging monastic orders and built churches expressly for them such as Santa Croce for the Franciscans (Fig. 15.7) and Santa Maria Novella for the Dominicans in Florence (Fig. 15.8); Siena also built separate churches for these two orders. Similarly, the cities each built cathedrals (Fig. 15.5) claiming to be more beautiful than the other. Siena's Cathedral was of French Gothic design: Florence's Santa Maria Novella was more austere, with plain façade and simple interior. Siena and Florence were both thought to be watched over by the Virgin Mary, as evidenced by the frescos of the period.

Since trade was the foundation for both communities, the supremacy of the guilds was paramount. In Siena the merchant's guild was the most powerful while in Florence the banking, lawyers, and wool guilds were the strongest. It was the Florentine bankers who first introduced a single currency in Europe, the gold florin. Only guild members, perhaps the head of the guild, could serve in the government. As the fortunes and powers of the guilds rose and fell, so did the government. In both cities, a marriage of church and government prevailed.

Tuscan Religious Life

The two new monastic orders, the Dominicans (founded by St. Dominic from Spain) and the Franciscans (founded by St. Francis of Assisi (fig. 15.9) in Italy), were mendicant orders, meaning that they neither held property nor engaged in business. Rather, they relied on contributions from their communities to support them. Unlike the monastic Benedictine order, they were dedicated to working with the common people. Noble families contributed to the building of monastic churches by donating a chapel thereby guaranteeing their salvation.

Painting in Siena and Florence

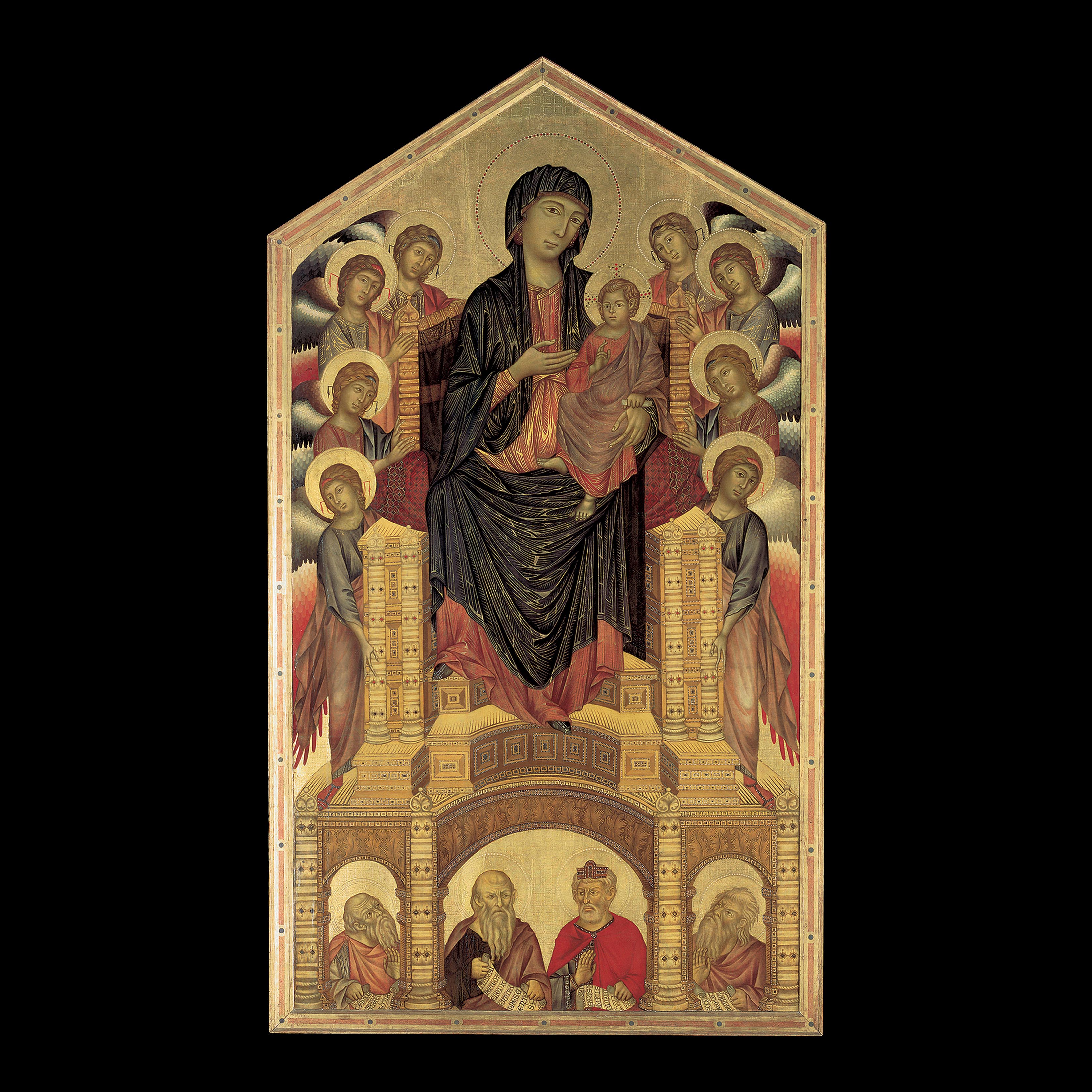

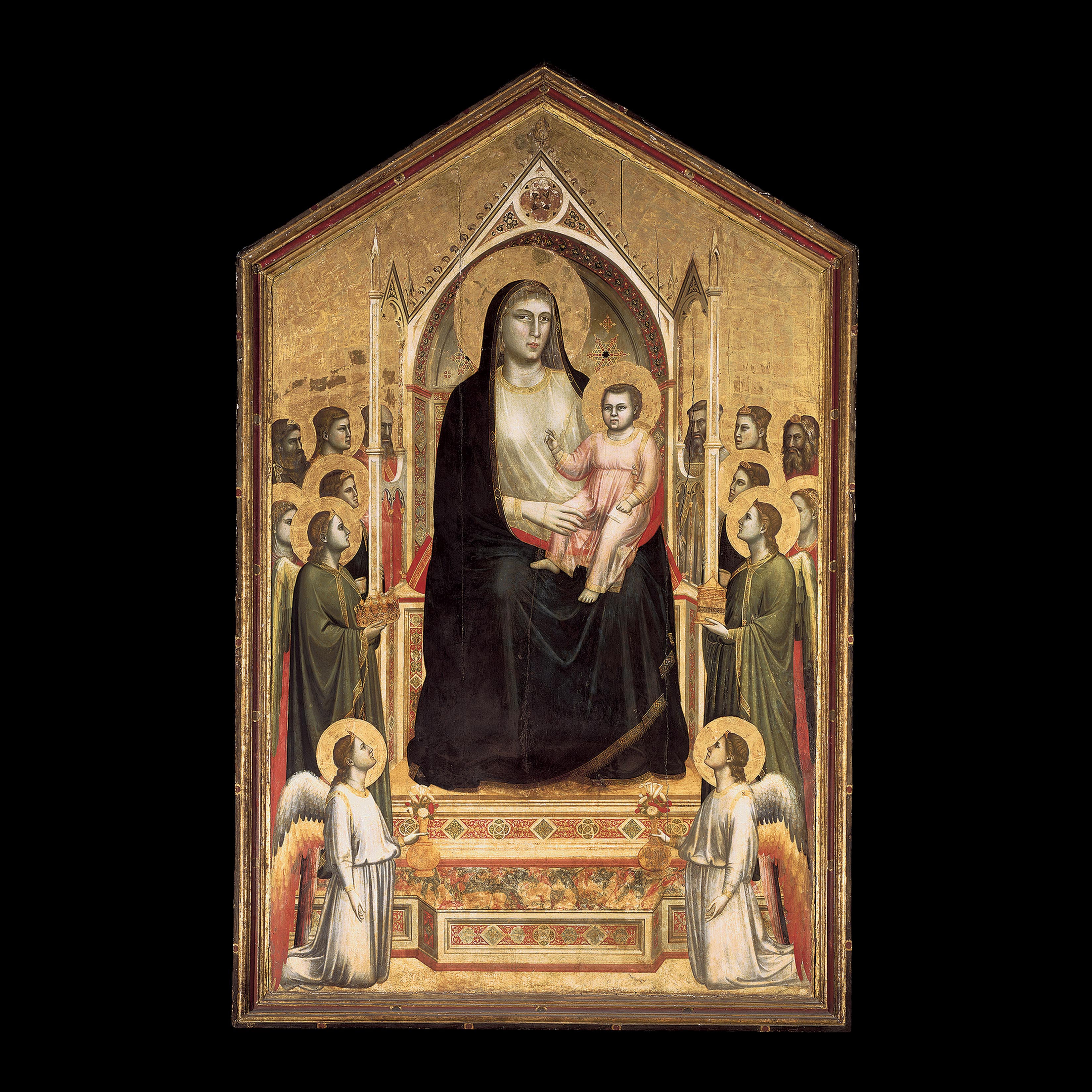

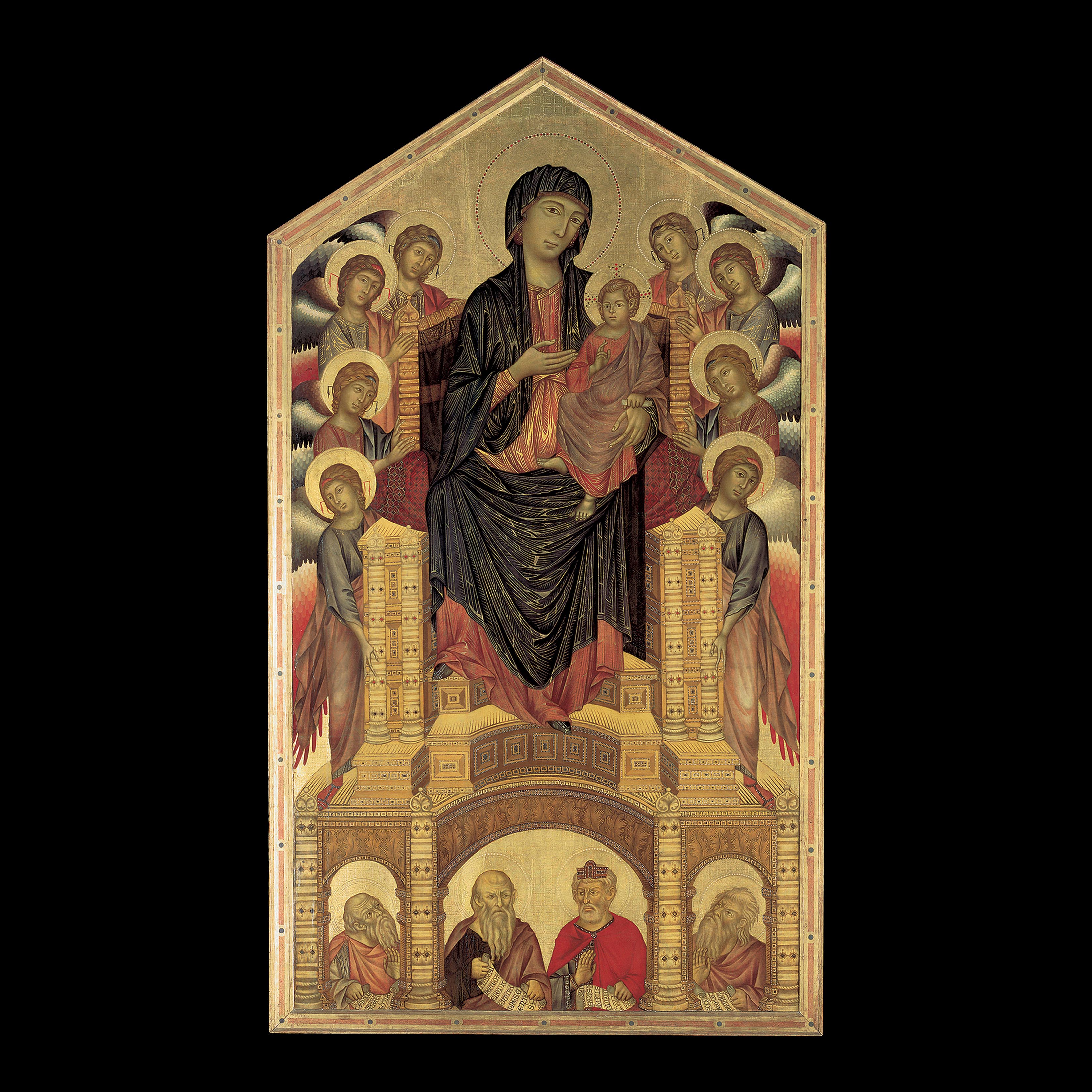

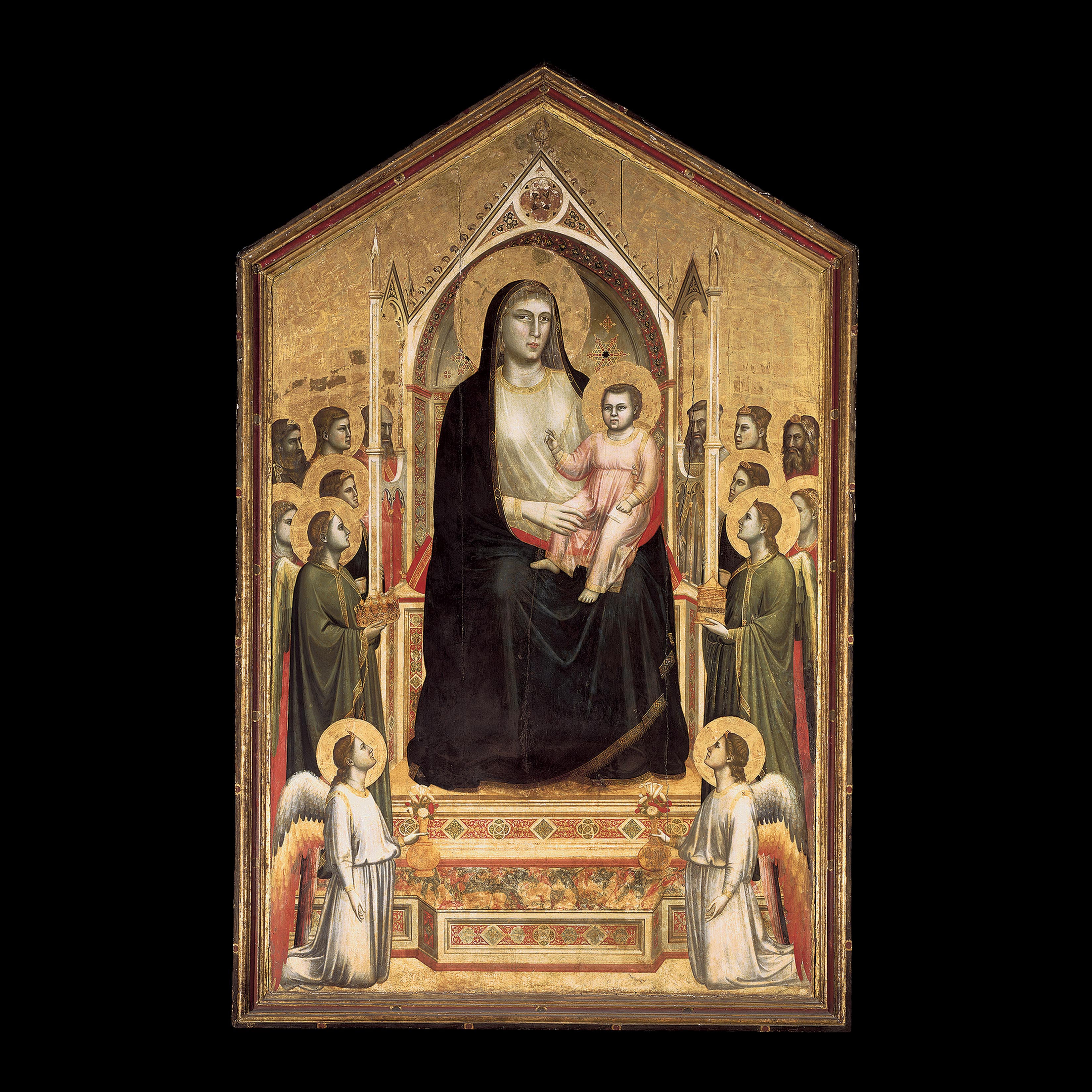

The competition between Siena and Florence was taken up by their artists, particularly those who were decorating the cathedrals and churches. The key figure was the Virgin Mary who watched over both cities and the rivalry was over the magnificence of her depiction. In Siena, Duccio' di Buoninsegna's rendering (Fig. 15.10) of space is much more natural, while Simone Martini's (Fig. 15.11) fresco establishes the "Queen of Heaven" motif in his painting of the Virgin Mary .

The story is told that Cimabue discovered a talented shepherd boy and tutored him in painting. That boy was Giotto and the student soon surpassed the teacher. In Florence, Cimabue (fig. 15.13) and Giotto fig. 15.14) were likewise painting figures with greater naturalism although the Byzantine influence of hierarchy is obvious. Ciamabue's concern was for spatial volume as well as naturalistic expressions. Giotto's depiction of the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ in the Arena Chapel brought an expressiveness and emotional symbolism to his work not seen in Western art since Hellenism. They are considered his greatest works. Giotto was the first artist to depict figures from behind. They were done in buon fresco, (wet plaster) rather than seca fresco (dry plaster). (Tempera - pigments mixed with egg yolk and water and painted on gesso based panels had been previously used). His colors re-create the realistic appearance of shadows as he blends from light to dark around contours of his figures.

The story is told that Cimabue discovered a talented shepherd boy and tutored him in painting. That boy was Giotto and the student soon surpassed the teacher. In Florence, Cimabue (fig. 15.13) and Giotto fig. 15.14) were likewise painting figures with greater naturalism although the Byzantine influence of hierarchy is obvious. Ciamabue's concern was for spatial volume as well as naturalistic expressions. Giotto's depiction of the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ in the Arena Chapel brought an expressiveness and emotional symbolism to his work not seen in Western art since Hellenism. They are considered his greatest works. Giotto was the first artist to depict figures from behind. They were done in buon fresco, (wet plaster) rather than seca fresco (dry plaster). (Tempera - pigments mixed with egg yolk and water and painted on gesso based panels had been previously used). His colors re-create the realistic appearance of shadows as he blends from light to dark around contours of his figures.

The Tuscan Vernacular Tradition

Early works such as The Song of Roland began a tradition of writing in the local or vernacular language instead of Latin, the language of scholarship. Dante Aligheri's Divine Comedy, written in Italian, is one of the greatest vernacular literary works in history. Dante imagines the travel of a Christian soul from Hell to Salvation, and peoples this world with real figures of the period and of antiquity, such as the Roman poet, Virgil, Caesar, Homer, Socrates and Beatrice, the love of his life. Of particular ingenuity is his creation of nine rings of hell as depicted in Inferno nine circles of Purgatory, and nine circles of Heaven. The Divine Comedy ends with Dante's understanding of and intense longing for God.

Early works such as The Song of Roland began a tradition of writing in the local or vernacular language instead of Latin, the language of scholarship. Dante Aligheri's Divine Comedy, written in Italian, is one of the greatest vernacular literary works in history. Dante imagines the travel of a Christian soul from Hell to Salvation, and peoples this world with real figures of the period and of antiquity, such as the Roman poet, Virgil, Caesar, Homer, Socrates and Beatrice, the love of his life. Of particular ingenuity is his creation of nine rings of hell as depicted in Inferno nine circles of Purgatory, and nine circles of Heaven. The Divine Comedy ends with Dante's understanding of and intense longing for God.

The Black Death

The significance of the Black Death (Bubonic Plaque) and its aftermath cannot be overstated. Besides the huge number of dead, about 25 million, society was fractured and trade was interrupted. The need for a scapegoat led to pogroms of the Jews, punishment of self by flagellants, and psychological effects, including doubt of the church. There were many artistic representations of the plague depicting skeletons, cadavers, graves and rotting corpses. These features were usually in the form of a memento mori, literally "What you are we were and what we are you will be."

Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron was set against the backdrop of the plague where the characters escape the death ridden city for the country to wait out the passing of the disease or their own death. The use of vernacular language highlights the immediacy of the tale and the stories are themselves imbued with a realistic representation of life as it is truly lived.

Chaucer was the first Englishman to translate Petrarch's work. His Canterbury Tales (Reading 15.9). though written in verse, heroic couplets, rather than prose, mirrors Boccaccio's in that stories are told by characters in need of diversion. The variety of people who tell their tales and the details of their stories present a realistic view of the era as Chaucer's characters come from all three estates, social ranks.

Chaucer was the first Englishman to translate Petrarch's work. His Canterbury Tales (Reading 15.9). though written in verse, heroic couplets, rather than prose, mirrors Boccaccio's in that stories are told by characters in need of diversion. The variety of people who tell their tales and the details of their stories present a realistic view of the era as Chaucer's characters come from all three estates, social ranks.

Many of both Boccaccio's and Chaucer's characters are women and they represent a new, increasing independence among European women. In the Tale of Filippa, Boccaccio has Filippa charge her husband with adultery as she declares there is a double standard for men and women.

Christine de Pizan became the first female professional writer in European history. She was educated in the French court and when her husband died and she was left with three children to raise, she turned to writing. In her Book of the City of Ladies (fig. 15.21), she attacked male misogyny by rehearsing the accomplishments of women throughout the ages.

Christine de Pizan became the first female professional writer in European history. She was educated in the French court and when her husband died and she was left with three children to raise, she turned to writing. In her Book of the City of Ladies (fig. 15.21), she attacked male misogyny by rehearsing the accomplishments of women throughout the ages.

They also supported the emerging monastic orders and built churches expressly for them such as Santa Croce for the Franciscans (Fig. 15.7) and Santa Maria Novella for the Dominicans in Florence (Fig. 15.8); Siena also built separate churches for these two orders. Similarly, the cities each built cathedrals (Fig. 15.5) claiming to be more beautiful than the other. Siena's Cathedral was of French Gothic design: Florence's Santa Maria Novella was more austere, with plain façade and simple interior. Siena and Florence were both thought to be watched over by the Virgin Mary, as evidenced by the frescos of the period.

They also supported the emerging monastic orders and built churches expressly for them such as Santa Croce for the Franciscans (Fig. 15.7) and Santa Maria Novella for the Dominicans in Florence (Fig. 15.8); Siena also built separate churches for these two orders. Similarly, the cities each built cathedrals (Fig. 15.5) claiming to be more beautiful than the other. Siena's Cathedral was of French Gothic design: Florence's Santa Maria Novella was more austere, with plain façade and simple interior. Siena and Florence were both thought to be watched over by the Virgin Mary, as evidenced by the frescos of the period.

The story is told that Cimabue discovered a talented shepherd boy and tutored him in painting. That boy was Giotto and the student soon surpassed the teacher. In Florence, Cimabue (fig. 15.13) and Giotto fig. 15.14) were likewise painting figures with greater naturalism although the Byzantine influence of hierarchy is obvious. Ciamabue's concern was for spatial volume as well as naturalistic expressions. Giotto's depiction of the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ in the Arena Chapel brought an expressiveness and emotional symbolism to his work not seen in Western art since Hellenism. They are considered his greatest works. Giotto was the first artist to depict figures from behind. They were done in buon fresco, (wet plaster) rather than seca fresco (dry plaster). (Tempera - pigments mixed with egg yolk and water and painted on gesso based panels had been previously used). His colors re-create the realistic appearance of shadows as he blends from light to dark around contours of his figures.

The story is told that Cimabue discovered a talented shepherd boy and tutored him in painting. That boy was Giotto and the student soon surpassed the teacher. In Florence, Cimabue (fig. 15.13) and Giotto fig. 15.14) were likewise painting figures with greater naturalism although the Byzantine influence of hierarchy is obvious. Ciamabue's concern was for spatial volume as well as naturalistic expressions. Giotto's depiction of the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ in the Arena Chapel brought an expressiveness and emotional symbolism to his work not seen in Western art since Hellenism. They are considered his greatest works. Giotto was the first artist to depict figures from behind. They were done in buon fresco, (wet plaster) rather than seca fresco (dry plaster). (Tempera - pigments mixed with egg yolk and water and painted on gesso based panels had been previously used). His colors re-create the realistic appearance of shadows as he blends from light to dark around contours of his figures. Early works such as The Song of Roland began a tradition of writing in the local or vernacular language instead of Latin, the language of scholarship. Dante Aligheri's Divine Comedy, written in Italian, is one of the greatest vernacular literary works in history. Dante imagines the travel of a Christian soul from Hell to Salvation, and peoples this world with real figures of the period and of antiquity, such as the Roman poet, Virgil, Caesar, Homer, Socrates and Beatrice, the love of his life. Of particular ingenuity is his creation of nine rings of hell as depicted in Inferno nine circles of Purgatory, and nine circles of Heaven. The Divine Comedy ends with Dante's understanding of and intense longing for God.

Early works such as The Song of Roland began a tradition of writing in the local or vernacular language instead of Latin, the language of scholarship. Dante Aligheri's Divine Comedy, written in Italian, is one of the greatest vernacular literary works in history. Dante imagines the travel of a Christian soul from Hell to Salvation, and peoples this world with real figures of the period and of antiquity, such as the Roman poet, Virgil, Caesar, Homer, Socrates and Beatrice, the love of his life. Of particular ingenuity is his creation of nine rings of hell as depicted in Inferno nine circles of Purgatory, and nine circles of Heaven. The Divine Comedy ends with Dante's understanding of and intense longing for God. Chaucer was the first Englishman to translate Petrarch's work. His Canterbury Tales (Reading 15.9). though written in verse, heroic couplets, rather than prose, mirrors Boccaccio's in that stories are told by characters in need of diversion. The variety of people who tell their tales and the details of their stories present a realistic view of the era as Chaucer's characters come from all three estates, social ranks.

Chaucer was the first Englishman to translate Petrarch's work. His Canterbury Tales (Reading 15.9). though written in verse, heroic couplets, rather than prose, mirrors Boccaccio's in that stories are told by characters in need of diversion. The variety of people who tell their tales and the details of their stories present a realistic view of the era as Chaucer's characters come from all three estates, social ranks. Christine de Pizan became the first female professional writer in European history. She was educated in the French court and when her husband died and she was left with three children to raise, she turned to writing. In her Book of the City of Ladies (fig. 15.21), she attacked male misogyny by rehearsing the accomplishments of women throughout the ages.

Christine de Pizan became the first female professional writer in European history. She was educated in the French court and when her husband died and she was left with three children to raise, she turned to writing. In her Book of the City of Ladies (fig. 15.21), she attacked male misogyny by rehearsing the accomplishments of women throughout the ages.